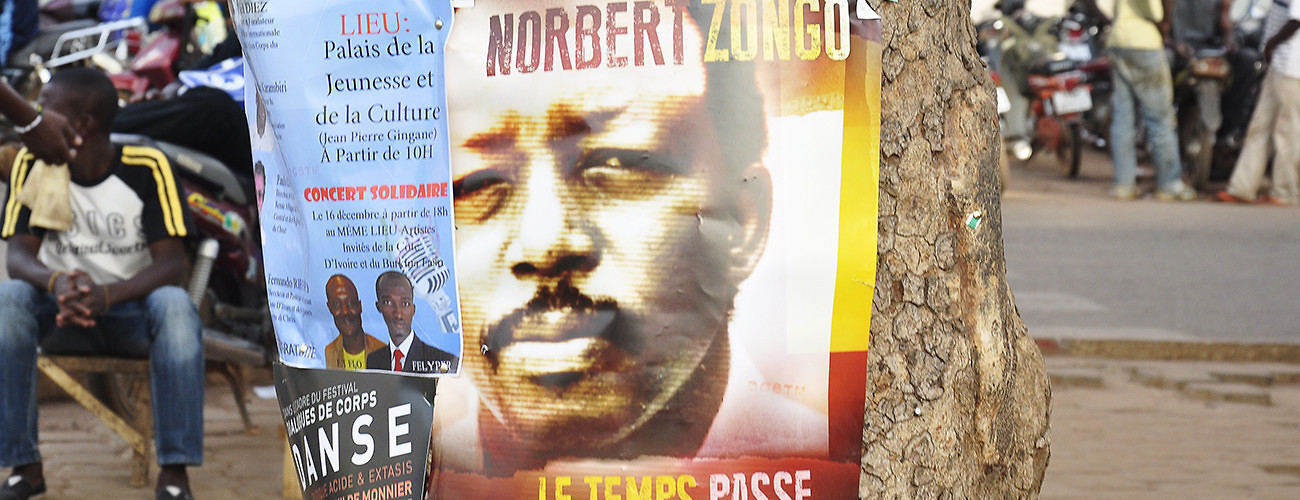

A poster baring the portrait of late journalist Nobert Zongo is attached to a tree as his supporters take part in a rally to mark the 14th anniversary since his murder and to demand justice and a fair investigation, in Ouagadougou, on December 13, 2012. (Ahmed Ouoba/AFP/Getty Images)

On June 5, the African Court on Human and People’s Rights ordered the government of Burkina Faso to pay damages to the beneficiaries of slain journalist Norbert Zongo and to re-open the domestic legal investigation into Zongo’s death. The Open Society Institute’s Chidi Odinkalu has analyzed the legal aspects of the case. He writes, “These are the most extensive measures of reparation ever to be considered or issued by the African Court.” Alongside its legal importance, the case has tremendous political importance for Burkina Faso.

On December 13, 1998, Zongo, editor of L’Indépendant, was found murdered along with his brother Ernest and two colleagues, Abdoulaye Nikiema and Blaise Ilboudo. Zongo had been investigating another death, that of a chauffeur for the family of then-President Blaise Compaoré. Many observers have long suspected that Zongo’s murder was carried out in order to stop his research into the corruption and wrongdoing of the regime. After Zongo’s death, Burkina Faso’s judicial system repeatedly stalled when it came to finding and prosecuting his killers. In 2001, a judge charged a senior member of the presidential guard for Zongo’s murder, but in 2006 the courts declared the case closed due to a supposed lack of evidence, outraging Zongo’s family and supporters.

Since his death, Zongo has symbolized resistance to one of the most tenacious regimes in Africa. Compaoré ruled from 1987 to 2014, and at times seemed invincible. Other coup leaders in West Africa came and went, such as Nigeria’s Sani Abacha (ruled 1993-1998), while civilian presidents were prone to coups themselves, such as Niger’s Mamadou Tandja (ruled 1999-2010) and Mali’s Amadou Toumani Toure (ruled 2002-2012). Meanwhile, Compaoré swept elections in 1991, 1998, 2005, and 2010. In 2005, he blocked an attempt to prevent him from running, claiming that the two-term limit imposed by the 2000 constitution did not apply retroactively. He weathered major protest waves in 2008 and 2011. He sought to position himself as a regional negotiator and statesman who would be indispensable to the stability of Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, and the broader region. His attempt to remove constitutional term limits in 2014 seemed guaranteed to succeed. Until the final days of the revolutionary protests of October 2014, many observers expected Compaoré to defy the protesters and impose his will on a pliant National Assembly.

As opposition to the regime built over a period of years, anti-Compaoré protesters repeatedly invoked Zongo, along with Captain Thomas Sankara. The latter was a leftist revolutionary leader whose four-year rule in Burkina Faso sought to remake the country as an economically and politically self-sufficient utopia. Compaoré, initially a companion of Sankara, toppled him in a 1987 coup in which Sankara was murdered. To many, Sankara represents Burkina Faso’s lost dreams, while Zongo illustrates the costs of Compaoré’s rule, especially in terms of corruption and human rights abuses.

The tenth anniversary of Zongo’s death in 2008 saw protests, adding to a tumultuous year in which urban residents rioted over high food prices; rioters directed much of their anger at Compaoré’s government. Three years later, Burkina Faso experienced even more serious unrest, with a combination of mutinies and protests shaking the country throughout the spring. The protesters, who called for an end to Compaoré’s rule, frequently invoked Zongo, along with Sankara. Even before Compaoré fell, the BBC noted “signs that [Sankara’s] legacy [was] enjoying a revival,” including through “the household brooms being wielded at street demonstrations in Burkina Faso” – a sign of the need to clean house.

Given the symbolic and political importance of Zongo and Sankara, it is unsurprising that in post-revolutionary Burkina Faso, activists have demanded new efforts for justice. When activists pressure the new, transitional government led by Acting President Michel Kafando to resolve the cases, they are seeking not just to memorialize the past, but to test the new authorities’ commitment to transparency. As the Committee to Protect Journalists has written, Zongo’s murder is still an “open wound.” That was demonstrated by Kafando’s disastrous decision to appoint Adama Sagnon, the former prosecutor in the Zongo case, as minister of culture in November 2014; within forty-eight hours, Sagnon resigned under pressure from activists. Speaking at Burkina Faso’s independence day on December 11, Kafando said that the cases of both Zongo and Sankara would be re-opened. Activists kept the pressure on. For the sixteenth anniversary of Zongo’s death on December 13, 2014, just six weeks after Compaoré fell, thousands of protesters marched, calling for a fresh investigation.

The new government has also taken action–and faced pressure–with regard to Sankara. In May 2015, responding to a long-standing demand from Sankara’s family, the authorities began to exhume graves in order to seek and verify Sankara’s remains. Sankara’s widow Mariam returned to Burkina Faso the same month for only the second time since 1987. She gave testimony to a military court handling the renewed inquiry into Sankara’s death. Meanwhile, Sankara is once again a figure of much discussion and admiration in Burkina Faso and across Africa–meaning that the new government will need to tread carefully when it comes to managing his memory.

The African Court’s judgment on the Zongo case this month has placed the responsibility for justice firmly on the new government. Given that activists are not content with mere promises of legal action, the new regime’s performance in investigating Zongo’s and Sankara’s deaths will be one bellwether of its relationship with the protesters who toppled Compaoré. Both men symbolized not only the hopes of many Burkinabé for a more open and prosperous society, but also the frustration of the country’s citizens at the ability of the powerful to prevent accountability for crimes. Burkinabé, as well as many other Africans, are watching to see how post-revolutionary Burkina Faso will negotiate the politics of memory, and whether and how the country can guarantee justice for two key opponents of the toppled regime.