Members of ISIS (Flickr/Day Donaldson)

The attraction of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) despite—or because of—its unapologetic brutality has prompted renewed international efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism through civilian-led responses rather than solely traditional law enforcement methods. Part of the effort has been to challenge the legitimacy of extremist narratives or provide positive alternatives aimed at reducing the appeal and recruiting power of groups like ISIS. For example, the Europe-based Sisters Against Violent Extremism aims to “develop alternative strategies for combating the growth of global terrorism” and challenge extremist thinking through critical debate. As the ranks of foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria continue to swell, the need to focus more proactively on prevention strategies such as these has grown.

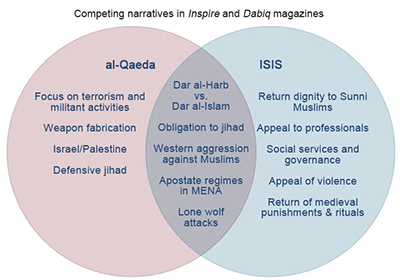

Many efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism focus on the establishment of “counternarratives.” The idea being to challenge or delegitimize the myths and narratives of extremist ideologues, thereby lessening their appeal and, in the case of jihadist groups like ISIS, stemming the flow of foreign fighters and funding. A number of attempts appear to be premised on the notion that jihadist groups are selling the same story and targeting a similar demographic. This is true to some extent: Groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS have honed a sophisticated communications strategy that links local grievances and dynamics to a global master narrative—they’ve gone “glocal.” Beyond this tailored approach, however, they are also selling two different stories or opportunities, and understanding this difference is critical to the development of effective preventive and responsive measures.

The similarities between the al-Qaeda and ISIS narratives include the focus on the obligation to perform jihad by all able-bodied Muslims. In both al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s publication Inspire and ISIS’s Dabiq the concept of abandoning or abstaining from jihad while proclaiming to be Muslim is seen as hypocrisy. Both organizations also portray the West (particularly the United States) and its allies as nations that are hostile to Muslims. Al-Qaeda and ISIS both frame their ideologies within the conception of Dar al-Harb (house of war) and Dar al-Islam (house of Islam), which, within the Salafi literalist context, asserts the incompatibility of Islam with secular law and governance.

The critical difference between the two groups that needs to be a key factor in counternarrative strategies concerns their ultimate aims. While al-Qaeda portrays itself primarily as a militant group—a covert, almost Delta Force-like organization of specialized fighters and operational masterminds—ISIS’s narrative draws on the discourses of statebuilding and governance, with a more established goal of creating and managing a Utopian state and calling for doctors, cleaners, and others to contribute in their own capacities. Recent reports even suggest ISIS is distributing food aid to Syrian refuges, stamping its logo on World Food Programme supplies.

Al-Qaeda’s Inspire features three primary focus areas that can be considered the essence of the organization’s narrative. The first is a focus on militant activities and terrorism through the glorification of martyrs and the glossy documentation of successful operations. There is almost a complete absence of literature discussing concepts such as zakat, jizya, or dawah, which can be loosely defined as charity from Muslims, taxation of non-Muslims, and preaching of the Islamic faith. The second notable feature of Inspire is its utility as a DIY guide for weapon assembly, with each issue containing detailed instructions for fabricating bombs and other tools of terrorism. Lastly, the magazine promotes the perpetration of “lone wolf” acts of terror by individuals that can have absolutely no formal association with al-Qaeda. In sum, the narrative found in Inspire is one primarily focused on violent, punitive, and retaliatory actions against the West and lacks consideration toward any specifics of Islamic governance.

In contrast, the narrative espoused in ISIS’s Dabiq is largely focused on building an actual state based on a radical, or takfiri, interpretation of Islam reflected in the group’s slogan baqiya wa tatamaddad (remaining and expanding). Though ISIS also encourages lone wolf-style terrorism, the magazine issues multiple appeals for doctors, engineers, and professionals to make hijrah (migration) in order to assist in the construction of an Islamic government. The narrative sculpted by ISIS rests heavily on the ability to govern, as illustrated by its numerous articles discussing the social services, security, and dignity provided to Muslims under the Caliphate it has proclaimed. Consistent with the beliefs of the group’s forefather Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, ISIS’s narrative is sectarian in nature and promotes extreme prejudice against those deemed un-Islamic. This is clearly illustrated in the group’s assertion that it is the obligation of Muslims to destroy Shiite shrines, tombs, and mosques when possible. This narrative has also attracted other jihadists such as disaffected Taliban commanders and members from Pakistan and Afghanistan.

It is important to note that the approach to violence is also different for both groups. Al-Qaeda, and particularly Bin Laden’s early communications, portrayed a defensive jihad, a battle to promote and protect the ummah, or global Muslim community, from the onslaught of the West. While certainly there was unforgivable violence and attacks on non-combatants, there was also some attempt in the rhetoric to justify this or even contain the repercussions. Consequently, al-Zarqawi’s bloodlust in Iraq met the condemnation of leaders and members of al-Qaeda’s inner circle, who appeared to have been concerned that the sheer brutality of such campaigns would alienate key followers. In contrast, ISIS appears to revel in its savagery, and the hostile treatment and killing of hostages appears to draw more recruits, even as it disgusts the world. As the New Yorker’s George Packer noted:

“The point isn’t to use the right level of violence to achieve limited goals. The violence is the point, and the worse the better. The Islamic State doesn’t leave thousands of corpses in its wake as a means to an end. Slaughter is its goal—slaughter in the name of higher purification. Mass executions are proof of the Islamic State’s profound commitment to its vision.”

What does this mean for policies and practices aimed at preventing and countering violent extremism and reducing the pool of recruits and resources for these groups? In the case of al-Qaeda, or at least the group as it existed under Bin Laden, reports of killing Muslims, unrestrained violence, poor treatment of members, and leadership fractures could prove useful in challenging the idealized myth of a defensive movement. In the case of ISIS, which presents itself almost as a “mass death cult” as Packer noted, these same measures may have little appeal, especially as more and younger recruits get their jihadist sound bites off YouTube and are less inclined to ponder the rationale of a “just war” doctrine. Counternarratives will need to focus less on the idea that support for the group is irrational and more on ISIS’s inability to meet the standards of leadership and governance, the bleak realities of the battlefield, and the inhospitality of the Caliphate to the very people it purports to hail as its citizens. To be successful, such efforts will require a much greater investment by governments and partners, who have so far continued to focus on militarized efforts that have little impact on changing the value systems and perceptions of vulnerable individuals or groups.

Naureen Chowdhury Fink (lead author) is Head of Research and Analysis at the Global Center on Cooperative Security. Benjamin Sugg is a Research Assistant at the Global Center on Cooperative Security and completing his graduate degree at Johns Hopkins University.