UN member state flags hang at the UN’s Vienna International Centre.

From Scotland to Syria to Somalia, various groups are seeking to create independent states. The Scots will vote on independence this September. Kurds in northern Syria and Iraq have revived their hopes for an independent Kurdistan as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) envisions redrawing the map of the Middle East. And tribal leaders in northwest Somalia govern the territory they claim more effectively than the internationally-recognized Federal Government of Somalia controls the south.

While their domestic contexts may be dramatically different, the broader political aims of these groups are part of a larger trend of rising secessionism. Secessionism has been on the rise since the mid 20th century, and in 2014, there are over 50 secessionist groups around the world. Why do so many groups seek statehood today?

When the UN was founded in 1945, it had 51 members. In 2014, the General Assembly is comprised of 193 member states, with an additional two non-member states as permanent observers. This explosion in the number of sovereign states has been a product of secessionism. And with each new state comes the possibility of new secessionist movements.

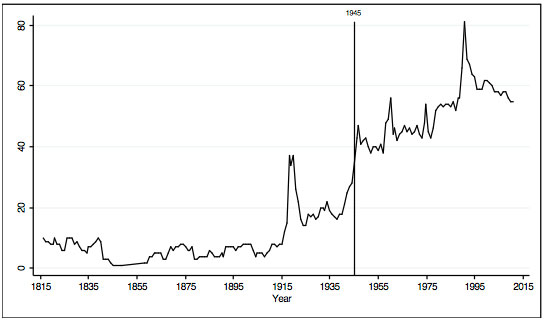

Figure 1: Annual Number of Secessionist Movements, 1816-2011

|

As we discuss in a recent article in International Studies Review, secessionism has risen dramatically since World War II. Between 1816 and 2011, we identify 403 secessionist movements–groups of people within a state that actively seek to break away from the larger country and obtain independence. In the years prior to 1945, the average annual number of secessionist movements was less than nine; in contrast, the average number after 1945 has been 51, more than a five-fold increase. That the number of movements has generally increased over the post-1945 period, even as the number of sovereign states has increased, speaks to a high rate of secessionism: new movements are springing up to replace those that succeeded in gaining their independence.

A changing international environment has made statehood more attractive for aspiring nations. Membership in the club of sovereign states has always brought privileges, but these perks are increasing in number and improving in quality–and secessionists know it. The rise of a norm against territorial conquest and multilateral organizations that support this norm have provided a safe haven of sorts for newly independent states. Newborn states today, like Montenegro, can gain membership to organizations such as the UN; this membership offers some protection against predatory neighbors, more so at least than was afforded to new states in the 19th or early 20th centuries. Secessionists are also helped by the international community’s stated allegiance to the principle of self-determination, which lends legitimacy to their cause and also provides language in which to present it.

Today’s new states also enjoy a host of economic benefits unavailable to their predecessors. Smaller states such as Singapore can plug into the global economy to attract international finance. Aspiring nations like Bougainville pin their post-independence economic policies to key extractive industries like copper mining. Moreover, international aid provides a financial safety net for newborn states that may be economically insecure. But, as the secessionist government in Somaliland knows, multilateral aid agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) cannot give loans to breakaway regions until they are recognized. Aid is one more perk of sovereign statehood, and young states like Eritrea, East Timor, Montenegro, and Kosovo were quick to apply to the IMF after gaining independence.

Secessionists often have a sophisticated understanding of the rules–explicit and implicit–for gaining international recognition. We interviewed representatives of key international organizations, leaders of a number of secessionist movements, and consultants who provide legal and strategic advice to these movements. Secessionist groups treat international law strategically, often hiring outside diplomats (as in Kosovo and Somaliland) and/or developing a corps of international lawyers (as in Nagorno-Karabakh). Improvements in transportation and communications technology also mean that today’s secessionists are typically well-networked with other aspiring nations.

This surge of secessionists presents a series of dilemmas for the international community. Most secessionists use non-violent means to advance their claims, but recent research suggests that while non-violence is generally more politically effective than violence, this is not the case for secessionism. A majority of civil wars today are already driven at least in part by claims of self-determination–the international community thus faces the challenge of persuading secessionists to remain nonviolent, even though it is the violent secessionists who tend to be let into the club of states. In deciding whether to recognize a particular secessionist movement, individual states and the international community more broadly must also determine how representative that movement is. If the group gains statehood, will the benefits of recognition reach average citizens, or will they line the pockets of the new state’s political leadership? The increasing number of secessionist groups today often control large and important swathes of territory and people. In order to conduct the growing business of not-quite-international relations, new modes of diplomacy may be needed to redirect at least some of the benefits of statehood without redrawing large portions of the world map.

Tanisha Fazal is Associate Professor of Political Science and Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Ryan Griffiths is a lecturer in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.