The opening of a polling station in Kiev, May 25, 2014. (OSCE Parliamentary Assembly/Flickr)

After months of speculation and intense analysis of numerous public-opinion surveys conducted in Ukraine as the crisis in that country has unfolded, we now have official results from the poll that really counts: an election, specifically the highly anticipated special election for the presidency of Ukraine held on May 25. In some respects, the fact that this election was held at all should be seen as a success, especially since a clear-cut winner, Petro Poroshenko, emerged (obviating the need for a runoff). Further good news was the pathetic showing of the ultra right wing or hyper-nationalist candidates, debunking the Russian-perpetrated myth that “extremists” and “fascists” were taking over Ukrainian politics.

The European Union quickly praised the election and pledged to work together with the victorious Poroshenko. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), which had deployed a large monitoring team for the election, likewise endorsed the vote and seemed pleased with the outcome. Even Russia made nice, with its foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, saying, “We shouldn’t miss the chance that we have now to establish an equal dialogue of mutual respect considering the vote that has taken place, the results of which Russia is ready to respect.”

Notwithstanding issues about the president-elect himself, the daunting prospects for fixing Ukraine’s broken economy, the gigantic unpaid bill for Russian natural gas, the pressing need to clean up rampant corruption, the dysfunctional national legislature, and, of course, suppressing the armed revolt in the eastern oblasts (regions) of Donetsk and Luhansk with no viable military or internal security capability at the government’s disposal, one ought at this point to ask what we can take away from this election in terms of its legitimization (or not) of the incoming administration. As will be discussed below, although there are some encouraging signs here for Ukraine going forward, the results also contain disquieting aspects that should temper the upbeat headlines and official enthusiasm for the outcome.

US Secretary of State John Kerry, in an interview on the PBS NewsHour which aired on May 29, said that the US planned on backing a “…new president, elected by the vast majority of the people of Ukraine.” That’s a positive, forward-looking policy endorsement for this new leader, and it would be nice in the first instance if that description of the election results were true.

But it isn’t. Here are the basic facts. Right around 30 million people were eligible voters in those parts of Ukraine where it was actually possible to cast ballots; that is, the total number of voters nationally (some 35.5 million) minus the seceded Crimea (and the federal city of Sevastopol) and those districts within Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts where separatists prevented any voting. Out of that approximately 30 million, around 18 million people cast ballots, for a turnout of about 60 percent. Of that number, 9.86 million (54.7%) voted for Poroshenko, or roughly one out of three potential electors; surely not “the vast majority,” but enough anyway.

And although the national turnout was lower than in the previous two first-round Ukrainian presidential elections (81% in 2004 and 67% in 2010), under the circumstances and on the surface it seems reasonable and, by comparison, in line with the 2008 and 2012 US presidential elections.

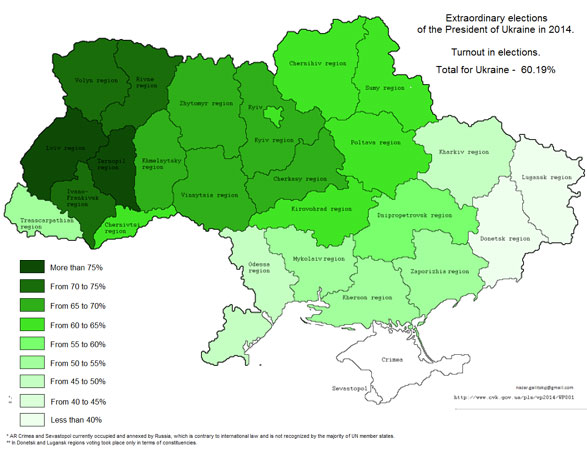

But as is true with all large countries, and especially with Ukraine, those national results need to be broken down by regions, and this is where things definitely become less rosy. For those who are concerned about the territorial cohesiveness of Ukraine, the regional pattern of voter turnout on May 25, as shown in the map below, once again raises the familiar specter of a western-to-eastern gradient across the country in terms of an important indicator which, in the absence of strong unifying national institutions, could be problematic.

|

Source: Central Electoral Commission of Ukraine. Map by Nazarij Galitskiy |

Leaving aside Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts where participation was understandably very low, note that voter turnout was below 50 percent in Odessa oblast in the south and in the crucial, heavily populated Kharkiv oblast in the east, and below the national average in the other oblasts in the south and east (Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhya, Kherson, and Mykolaiv) as well. These levels represent a significant drop in turnout in these units compared to the 2010 presidential election, in most cases by double digits. By contrast, 2014 voter turnout was well above average in the western regions of Ukraine and above average in the central regions, in some cases with major gains over the already high turnout evidenced in 2010. At the extremes (not counting Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts) for the 2014 vote (Lviv oblast in the west at 78.2 percent turnout and Odessa oblast in the South at 46.0 percent) there is a disparity of over 32 percentage points in turnout; in the 2010 voting, the inter-regional turnout gap was just 17 percentage points.

Compounding these spatial disparities in voter turnout is the fact that Poroshenko ran relatively poorly in the oblasts with lower participation. Thus, right across these southern and eastern oblasts he came nowhere near his national average, and in some cases, especially in the Zaporizhya oblast and, again, the very important Kharkiv oblast, he garnered only 38 and 35 percent of the vote respectively.

So what can we take away from these figures? Does this higher (or lower) turnout among the regions suggest stronger (or weaker) confidence in Ukraine as a state? First, this was a special (i.e., unscheduled) election held under extraordinary circumstances by an interim government, a situation that could be expected to depress turnout. But these circumstances did not suppress turnout in the western and central parts of the country; on the contrary, as mentioned above, some regions manifested very high participation rates, in many cases higher than in previous elections. We know from the work of Erik Herron and Nazar Boyko that preparations for the May 25th special election were not proceeding smoothly in many areas of the country, with administrative and staffing problems somewhat more problematic in the southern and eastern regions, so these logistical issues, or greater proximity to regions where actual violence was occurring may partly account for lower voter participation.

Yet turnout exceeded the national average in some western regions where there also were clearly administrative problems. Pre-election surveys showed that relatively fewer voters in the southern and eastern regions stated that they were likely to vote (or that more felt pressured not to vote), suggesting that lower turnout in these areas was already in the offing. If voters stayed away from the polls because they questioned the validity of the election, the country’s many problems will be much tougher to solve. On the other hand, if this regional disparity in voter participation turns out to be a passing phenomenon caused mainly by a separatist movement (that might eventually be staunched) and the administrative challenges of staging a national election under such trying circumstances, then prospects for the future would appear brighter.

Most Ukraine watchers expect that President Poroshenko will call for early elections to the country’s legislature (the Rada), probably this fall. If so, we may have another opportunity to see to what degree Ukraine’s electors across the regions choose to participate in the democratic process, with the country’s future as a legitimate state on the line.

Dr. Ralph S. Clem is Emeritus Professor of Geography at Florida International University.