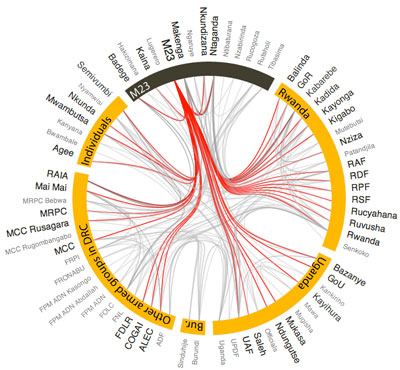

A screenshot of a new data visualization shows in red the connections between the rebel group M23 and various armed actors. See the visualization in action >>

For more than two decades, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has suffered from what is described as Africa’s “great war.” Two weeks ago, the United Nations Security Council renewed sanctions against the country. There are myriad factors fueling the country’s protracted conflict, and there is a bewildering assortment of armed groups keeping the embers burning. But who, really, is driving the conflict on the ground? How do they operate? And why do efforts to bring peace so regularly fall flat?

Outsiders and insiders alike have devoted years to trying to understand the persistence of DRC’s violence entrepreneurs. Many scholars have broached the issue from sociological, political, and other social science perspectives. And while their approaches have generated important insights, new thinking could help clarify the situation further still. A new dataset and interactive visualization that we created for the Stability journal could help shed some light on the protagonists of Congo’s interlocking conflicts.

The multidimensional dataset features detailed information on hundreds of armed groups, political elites, businessmen, and others. The information is drawn exclusively from a 2012 UN Group of Experts report that documents shady financial networks and the illicit procurement of military equipment. We developed a user-friendly data visualization to map the links between them, consolidating complex links in a single convenient snapshot (see above image.)

For example, one of the key protagonists of DRC’s latest round of fighting is the Mouvement du 23 Mars (M23), a rebel group formed in April 2012 in the wake of a failed peace agreement penned a few years earlier. With ready access to military-style weaponry, stolen cobalt and copper, and ties to other Congolese militants, the M23 emerged as one of the most formidable fighting forces in the DRC. From the beginning, there was evidence that M23 was backed by extensive foreign support.

The extent of assistance provided by foreign governments to the M23 has been the subject of much acrimony. Among the most controversial claims is that the rebels received direct military intelligence, assistance, and equipment from neighboring Rwanda and Uganda. If the allegations are true, then governments in both countries are violating an international arms embargo. Beyond these well-known allegations, the visualization also shows the extent and variety of other armed groups and individuals intertwined with the M23, which has established pacts with armed groups in the Kivu, Ituri and Kasai-Occidental provinces of the DRC, for example. All the while, the M23 has carried out brutal attacks, executed prisoners of war, and recruited child soldiers.

The M23 movement quickly reached its apogee with the fall of the Congolese city of Goma on November 20, 2012. Within a year, the group experienced a similarly speedy demise with its defeat by Congolese armed forces and a new UN intervention brigade. In spite of plans to quickly disarm and demobilize the group, a UN Group of Experts found that a number of sanctioned M23 leaders were still moving about freely in Uganda. Adding insult to injury, the rebels attacked UN peacekeepers and also demonstrated continued ties to Rwanda, openly recruiting new members in that country despite declaring an end to their rebellion in November 2013.

Owing to an apparently resurgent M23, the Security Council unanimously voted to renew its arms embargo and sanctions against the DRC last month. It also urged the UN and member states to increase their vigilance against former M23 combatants to ensure that the rebels did not regroup or resume military activities. A challenge for the international community, however, is keeping track of the individuals, governments, and networks sustaining the M23 in the DRC and outside of it.

The diplomats, soldiers, aid workers, and citizens working to bring peace to the DRC are only just beginning to appreciate the ways in which new technologies can change the landscape of peacebuilding. When prepared carefully, and with attention to local context, such tools may potentially revolutionize the way governments, non-governmental organizations, and international agencies understand and engage with questions of early warning and conflict prevention. By demonstrating the relationships between state and non-state actors and the manifold ways in which outsiders fuel civil wars, they can offer new ways to hold warring parties and recalcitrant armed groups to account.

Dr. Cathy Nagini has a PhD in medical biophysics with experience working in the DRC and on data visualizations. Robert Muggah has also worked across the Great Lakes and is the research director of the Igarapé Institute and directs research and policy at the SecDev Foundation. They co-authored the article in Stability with Mainak Jas and Hugo Fernandes.