In 1948, the UN Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) was deployed as the first United Nations peacekeeping mission, mandated to monitor the Arab-Israeli ceasefire. In the aftermath of World War II, the international system had evolved into a bipolar order in which international actors were focused mostly on interstate disturbances and proxy wars. During this time, organized crime was mostly concentrated in cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Naples, Palermo, and Tokyo, and of little significance to the international community. Peace operations and organized crime were separate and unrelated issues.

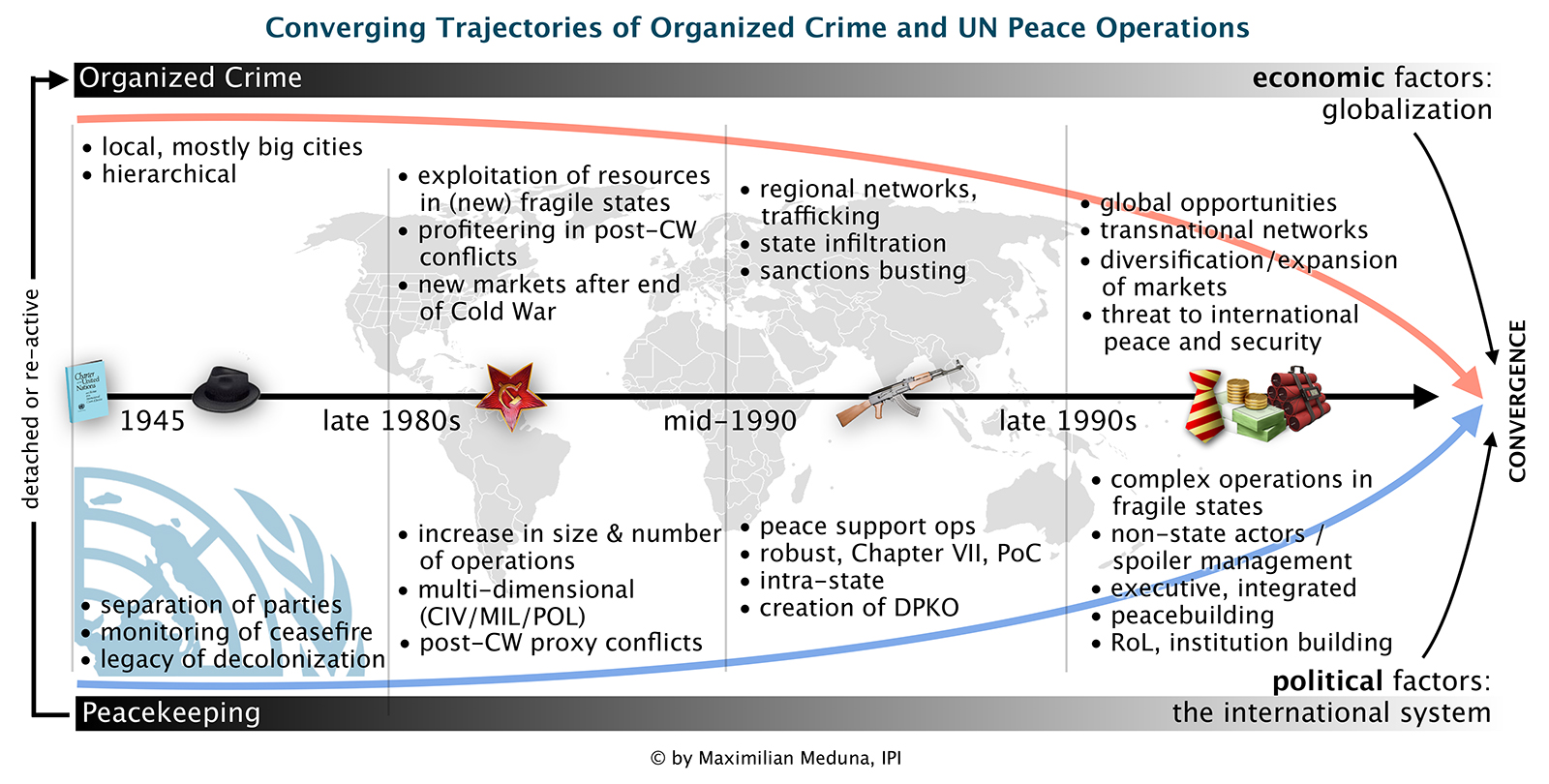

Sixty years later, however, as the international system changed and fragile states came into the spotlight, the trajectories converged. Both UN peacekeeping and organized crime have evolved over four distinct generations, adapting to their environment during similar time periods, despite the fact that organized crime was essentially driven by market forces, while peace operations came about as the result of primarily political developments and decisions.

A new report from the International Peace Institute, “The Elephant in the Room,” lays out this issue in depth. (The International Peace Institute also publishes the Global Observatory). It suggests that organized crime–in its various forms–is a serious threat to peace in virtually every theater where the UN has a peace operation or mission: from Afghanistan to Kosovo, from Mali to Somalia. Yet, out of 28 currently deployed UN missions, less than half have a mandate with an explicit reference to organized crime, and even most of these lack the resources to implement their crime-fighting mandates effectively.

Key Conclusions

- As indicated in the report, the main reason for the disconnect between peace operations and addressing organized crime can be found in the structural development of peacekeeping as a politically-driven process highly dependent on political will of sovereign states, while organized crime has flourished as an economically-fuelled phenomenon nourished by increasing globalization and state erosion.

- The report lists other causes of disconnect, including peacekeeping missions’ lack of appropriate mandates and response capabilities, the political expediency of senior UN and host government officials, and the lack of sufficient functional adjustment of “peacekeeping” as outlined below.

- The analysis in the report clearly reveals that the problem has been largely ignored, due to a lack of awareness or political will, a fear of its size and extent, and the difficulty of dealing with the challenge. “But ignoring the problem does not make it go away,” the report states—in fact, “it makes it worse.”

- It can be concluded from the report that UN peace operations have yet to fully adjust from a purely responsive mechanism to violent conflicts to a comprehensive strategy for stabilizing societies, including measures to address and eradicate organized crime. As trajectories of organized crime and peace operations converge, so too should operational responses—particularly in fragile states.

Analysis

Until the late 1980s, UN peace operations were conceived as a tool to monitor ceasefires in established buffer zones between warring parties. At that time, organized crime was seen by the international community as a relatively isolated problem mostly concentrated in cities that had not yet entrenched itself in fragile and conflict settings. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, a new and much larger generation of peace operations deployed across conflict zones in the developing world, mandated to cope with challenges of change in countries where superpower rivalry left a legacy of instability. At the same time, these conflicts and the end of the Cold War opened new opportunities for criminal groups—including “the exploitation of natural resources (drugs, diamonds, and timber) in fragile states,” as the report notes. A third generation of peace operations emerged in the mid-1990s, when protracted intrastate conflicts, civil wars, and spoiler groups necessitated more robust multidimensional deployments.

Several of the armed groups involved in these conflicts had established “close links with criminal groups, or were themselves engaged in illicit activities”—as economic globalization deepened, these groups successfully seized control of new trafficking routes and areas of operation. Responding to complex (almost exclusively intrastate) conflict scenarios in the late 1990s, peace operations evolved to include new complex tasks ranging from robust enforcement, peacebuilding, and stabilization to state or institution building and even the implementation of executive mandates—thus marking the fourth generation.

Civil-military integration became a central element of modern peace operations to address the political and security challenges of fragile states more effectively. But even then, peacekeeping did not converge with the trajectory of criminal groups diversifying their operations throughout the global economy and into emerging markets, capitalizing on new sources of revenue. These criminal groups “became powerful transnational, nonstate actors,” the report ascertains—and a new political factor in fragile states. In fact, criminal groups are controlling trafficking routes from Latin America through West Africa to Europe, from Afghanistan through Central Asia to Russia, or through the Balkans to Europe. Local mafia wars of the 1940s have been replaced by a broad portfolio of worldwide activities, ranging from trafficking in drugs, arms, and human beings, through money laundering and kidnapping, to piracy and counterfeiting. Crime has become global, economic, and political. It has become a serious threat to international peace and security.

The United Nations, however, in its prime responsibility to maintain international peace and security, has thus far struggled to integrate an effective response mechanism to organized crime in its increasingly complex mission mandates, ranging from multidimensional peace support activities to integrated peacebuilding tasks, such as the establishment of the rule of law, security sector reform, or even executive policing.

There is a pressing need to bridge the gap between peace operations and organized crime as a serious threat to peace. In post-conflict societies, for the sake of short-term stability, actors are reluctant to address the structural roots of organized crime, ignoring and thus exacerbating the problem. Indeed, organized crime “is not a scenario that the United Nations was created to deal with, but it is the reality confronting member states and the UN today.” It is the elephant in the room.

As the above chart shows, in 1945, organized crime was a phenomenon of a few mostly urban areas around the globe; today, crime has evolved into a global threat to peace and security. Regional spillovers endanger neighboring countries and interconnected trafficking routes affect people thousands of miles away.

And yet, the international response to the threat, especially in fragile states and (post-) conflict theaters, has not adapted appropriately. While “criminal groups have entered a post-Westphalian era,” the report observes, and become transnational in their reach, the international response remains local and state-bound, regional at best. While criminal groups are diversifying their markets and infiltrating politics and business, their role in generating and fuelling conflict remains widely disregarded, their structural rooting in political economies underestimated.

Currently, there are 28 United Nations peace operations, including political and peacebuilding missions, deployed by the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and the Department of Political Affairs (DPA), including the new United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) and the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), both launched this summer.

In Mali, for instance, the Secretary-General acknowledged in his March 2013 report that “terrorist attacks, weapons proliferation, drug smuggling and other related criminal activities” will continue to remain a threat to peace and stability, while UN Security Council resolution 2100 (2013), authorizing MINUSMA, expressed the Council’s “continued concern over the serious threats posed by transnational organized crime in the Sahel region.”

Despite awareness of the problem, neither the initial UN Office in Mali (UNOM) nor the newly deployed UN Mission, under which UNOM was subsumed, received an explicit mandate to address the challenge. The example clearly illustrates that as trajectories of organized crime and peace operations converge, so too should operational responses. This is particularly important in fragile states such as Mali or Somalia, where the political economy of illicit activities can have a destabilizing impact on the entire region.

Maximilian M. Meduna is a Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute