How is it that Kenyans, who have voiced consistent support for the International Criminal Court, voted for candidates who were about to be tried by the same court? The answer reveals a web of contradictions, partly fueled by Western government missteps.

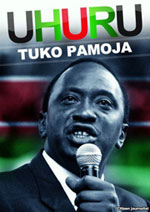

Many polls conducted since 2009 have shown that Kenyans supported the ICC. In October 2012, six months before the election, a Gallup poll found that 70% of Kenyans supported the ICC. But at the same time, the poll found that the majority of voters intended to support candidates who have been indicted by the ICC. The poll showed that 22% of those surveyed were going to vote for Uhuru Kenyatta, 15% for William Ruto, and 29% for Raila Odinga.

With all the wisdom one has in hindsight, that contradiction should have been looked at more carefully. There was tension between support for the ICC and a “don’t touch my candidate” type of attitude; this was the position of Kenyan public opinion as we moved into the heat of the election campaign.

Then, along came some Western powers. Shortly before the elections, the British High Commissioner declared that his country would maintain its policy on ICC accused, even if Kenyatta was elected. He said, “The policy of my government remains that we do not have contact with ICC indictees unless it is essential.” Kenyatta immediately seized upon this and accused Britain of playing a “shadowy” role in this election campaign. The European Union said that it would have limited contact with a president indicted by the ICC, thus supporting the British position. The US Assistant Secretary of State, Johnnie Carson, warned Kenyan voters that, “choices have consequences.”

These were statements which ministries of foreign affairs ought to have known would be perceived as self-righteous, arrogant, and condescending by many Kenyans. And that’s what happened.

Kenyatta—shrewdly, I think—used that vibe to whip up support, suggesting self-determination as an issue: here are these powers wanting to tell us Kenyans who to vote for, even though no direct allegations were made. The ICC became a major campaign issue, overshadowing other issues that you could find only in the manifestos of the parties if you took the trouble to look for them. Kenyan self-respect now seemed on the line, and Ruto and Kenyatta successfully exploited that.

While Western governments were right to emphasize the need for strict adherence to the principles of the Rome Statute, they could have achieved their objective by adopting the reasoning relied on by the Kenyan High Court shortly before the election; namely, that the suspects were presumed innocent until proven guilty and could therefore not be barred by the Court from standing as election candidates. In 2012, the lead prosecutor of the ICC at the time, Luis Moreno Ocampo, took the correct approach [pdf] in saying that Kenyan law must decide whether or not any suspects could run for office, and not the ICC.

When opposition parties asked Kenyatta how he planned to run a government and defend himself at the same time, Kenyatta said, “No problem, I can do them side-by-side.” He turned the ICC issue into a type of referendum for his supporters. He said, “You must give us an indication of what you think of the ICC and the process it has undertaken.” He sought a mandate, without spelling it out in direct terms.

In addition, there is much to be learned from the post-elections responses by major powers. The US Secretary of State John Kerry called the elections a “historic moment,” and said the US would “continue to be a strong friend and ally” of the Kenyan people. In fact, none of the responses referred directly to the victory of Uhuru Kenyatta—they all congratulated the Kenyan people. The British minister for Africa urged all sides to show restraint and expressed confidence in the courts. The European Union congratulated Kenyans for conducting a peaceful process and noted that the rule of law should be maintained at all times. The Canadian ambassador chimed in with similar sentiments.

China, however, congratulated President Kenyatta for winning the elections and Kenyans for voting peacefully. It indicated that it was looking forward to close cooperation with Kenya and with the new president-elect when he takes office: a very different approach.

The lessons are that governments who respond using a condescending approach towards developing countries can experience a backfire, and it has implications which both Kenya and those countries will have to struggle with. Kenya can’t afford sanctions or diplomatic pressures that could prejudice its development. Western powers regard Kenya as a country with major strategic importance in East Africa, and they still want to retain a close relationship even though the public fanfare around the president will not be the same. There will be contact, but at a more subdued level.

The ICC also represents a clash of interests between the political elites and the broad majority in Kenya. Among the Kenyan public—the ones who went through the 2008 election violence, who felt the impact of it—there has been strong support. But the political elite is strongly against the ICC. They see it as a threat, partially because it threatens political and criminal impunity. It potentially threatens their interests. In December 2010, Parliament unanimously adopted a motion calling for Kenya to withdraw from the Rome Statue, which would pull Kenya out of the ICC. This would have been a retrogressive step. Fortunately, the resolution was not binding, and there was a strong response and protest from civil society.

There is a danger that the elites will be able to strengthen their grip on politics, on the “public norms” as they are pronounced politically, and that the broad public will not see much of what they were hoping for: an end to impunity with help from an independent process through the Hague. The ethnic tensions below the surface are still very real. Kenya is in dire need of reconciliation and a dialogue to address the issue of ethnicity. If it were not for the significant support that now exists for the Supreme Court and the judiciary in Kenya, one would be pessimistic. That is one of the factors, which suggests that Kenya is a country with a future. The judiciary has broad support and the public has trust in it, and once institutions start having broad support and trust, developing countries are on their way to success, which I hope Kenya will be.

Peter Gastrow is a Senior Adviser at the International Peace Institute.