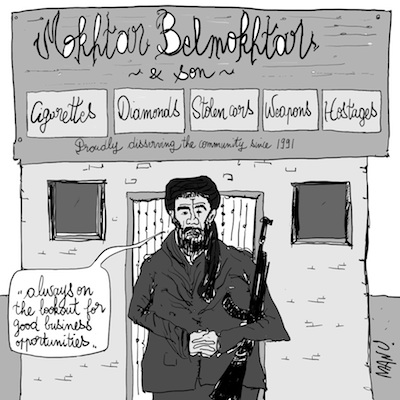

Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the Algerian Islamist militant behind the January 16th attack on a gas installation in southern Algeria, is an angry and busy man. One of his many nicknames, “Mr. Marlboro,” belies his cigarette-smuggling monopoly across the Sahel (other telling nicknames include “Laaouar”—meaning the One-eyed, the Prince, or the Uncatchable). Cigarettes, however, aren’t Belmokhtar’s only commercial commodity. He smuggles almost everything under the Saharan sun, from weapons to stolen cars to diamonds. But he is also a specialist in kidnapping Westerners and has allegedly received ransoms as high as $3 million a head.

Beyond Belmokhtar’s cohort, multiple Islamist groups are active in the western Sahel’s multimillion dollar kidnap-and-ransom industry. The most well known is al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)—the group Belmokhtar split from in 2012. AQIM received $5.4 million per hostage on average in 2011, making kidnapping its primary source of revenue. (AQIM also offers protection and passage services for smuggling networks.) The group’s expenses are commensurably high, with an estimated $2 million a month going toward weapons, cars, and payoffs for child soldiers, whose families receive a one-time payment of $600 plus a monthly payment of $400. In some cases, kidnappings are actually outsourced to smaller players. AQIM, for example, often pays other groups operating in the region for hostage taking, in order to capitalize on its own comparative advantage: financial settlements.

The kidnapping business offers the benefit of public and political leverage without as much stigma as other criminal activities: kidnapping can appear to “further jihadist goals, in contrast to involvement in the drug trade and other smuggling activities, which are out of the public eye and are seen to be purely criminal in nature,” according to a recent study (pdf). But reputation and brand recognition are critical to fully play that card, something that the jihadist corporations understood early on. For example, AQIM assumed its current name as part of a franchise agreement with the original al-Qaida. This agreement was mutually beneficial: it increased the mother organization’s global profile while boosting the notoriety of its otherwise independent regional franchises with a simple rebranding.

Yet, these entities and individuals are neither monolithic in their modes of operation nor single-minded in their motivations. For instance, while kidnap-and-ransom sits at the center of AQIM’s business model, al-Qaida is known more for its use of suicide attacks with mass casualties. At the same time, AQIM has successfully used kidnapped hostages to negotiate the release of jailed operatives (see this pdf report). These variations reflect the diversity of incentives behind kidnappings and hostage taking, in which both political and financial drivers are at play. Framing Belmokhtar as someone driven exclusively by greed would be misleading: he first ventured into international terror organizations at age 19 when he traveled to Afghanistan to train with al-Qaida to avenge the killing of the “father of global jihad,” Abdullah Yusuf Azzam. Since then, his long-time association with al-Qaida and splinter groups (and a son named after Osama bin Laden) have been indications of a clear ideological bent. Meanwhile, it is unlikely that Belmokhtar LLC is run as a not-for-profit organization motivated only by spiritual considerations. Either way, neither global jihad nor terrestrial pleasures are cheap.

From a business perspective, the kidnap-and-ransom enterprise is only as sustainable as the supply of “bankable” hostages. “It is the Western countries that are financing terrorism and jihad through their ransom payments,” Oumar Ould Hamaha told Reuters on behalf of the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO, also known as MUJWA), an offshoot of AQIM. When ransoms are paid, perpetrators and copycat groups are emboldened to continue kidnapping and ask for more money. An estimated $120 million were paid in ransoms to terrorists in the past eight years. If kidnapping is the “most significant terrorist financing threat today,” as asserted by US Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence David Cohen, it is partly a self-imposed one: “bankability” depends first and foremost on policy.

The US and the UK regularly communicate around their “longstanding policies” of not paying ransoms or making concessions with kidnappers. Although the possibility of settlements in some cases cannot be ruled out entirely, recent history does suggest that the UK and US’s typical response to kidnappings entails the use of force. Leaked cables from the US embassy in Bamako, Mali, indicated that AQIM had once offered to pay up to $100,000 for Westerners “so long as they were not American,” lending support to both the reality and efficiency of the policy. Other governments have traditionally been more willing to negotiate and pay. Many targets of kidnappings in the western Sahel in recent years have been French, Spanish, and Italian (see this pdf). Italy and Spain are alleged to have paid a ransom of $19.4 million for the release of three aid workers in 2011. AQIM is still demanding 90 million euro for the release of four French hostages kidnapped in 2010 in Niger while working for Areva, a French nuclear firm.

These differences in official or de facto policies stem from a complex web of political, cultural, and historical factors that cannot be easily singled out, nor changed. And in the case of the Algerian hostage crisis, the perpetrators were largely indiscriminate in targeting and murdering individuals of British, Japanese, Filipino, American, and Algerian nationality. The nature of their demands also remained relatively unclear—and they could actually have changed had the crisis dragged on. Clearly, no policy is fail-safe in the face of multifaceted and malleable motives. Other operational approaches to combat kidnapping for ransom include locating, freezing, and/or recovering assets, effectively denying kidnappers the fruits of their labor. This is no easy task, especially in contexts where governments have limited to no control over part or all of their territory.

The case of Mali’s northern territory is a critical and uncertain one. Along with the Islamist group Ansar Dine (not to be confused with the popular Sufi movement of the same name, the founder of which was quoted saying of the northern group, “This is not Sharia, but banditry”), AQIM and MUJAO controlled key northern cities until French and Malian forces launched a takeover in January. On January 31st, the French defense minister declared that seven French hostages kidnapped in Niger and Mali in 2011 and 2012 were likely held in the mountainous region north of Kidal, the “last Islamist holdout” to be taken over in the northeastern region. Five days earlier, a MUJAO spokesman had declared that the group stood ready to negotiate the release of one of them, kidnapped in western Mali on November 20th.

What happens next is also impossible to predict. Will the loss of turf by rebel groups simply displace or even intensify kidnapping activity and competition in other parts of the Western Sahel, or beyond? Historical evidence from crime reduction suggests this may not be the case. On the reasons behind the sharp drop in criminality observed in New York in the 1990s, Adam Gopnik wrote in the New Yorker that “criminal activity seems like most other human choices—a question of contingent occasions and opportunity….Close down the open drug market in Washington Square, and it does not automatically migrate to Tompkins Square Park.” If the analogy has any relevance, as it can be hoped, “Mr. Marlboro” may have to increasingly rely on the cigarette business.

Sarah Cramer is an independent development consultant. Emmanuel Letouzé is a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley and an independent development consultant currently serving as a Non-Resident Fellow at IPI. He is also a cartoonist and drew the above illustration.