“An effective accountability process will be as challenging for the new Libyan Government as it will be important for the future of the country,” said Ambassador Christian Wenaweser of Liechtenstein, President of the Assembly of States Parties to the ICC, during an interview with the Global Observatory.

“An effective accountability process will be as challenging for the new Libyan Government as it will be important for the future of the country,” said Ambassador Christian Wenaweser of Liechtenstein, President of the Assembly of States Parties to the ICC, during an interview with the Global Observatory.

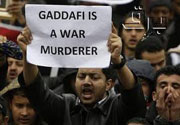

The question of how to bring to justice the perpetrators of crimes committed during the six-month civil war in Libya and during the 42-year rule of Qaddafi poses challenges to the newly configuring Libyan state.

The UN Security Council referred the situation in Libya to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in resolution 1970 on February 26th, providing it with a mandate to prosecute crimes committed after February 15, 2011. Arrest warrants have been issued for Muammar Qaddafi, his son Saif al-Islam Qaddafi, and intelligence chief Abdullah al-Senussi, but none of them has been arrested so far.

Key Conclusions

Responsibility to prosecute and try the Libyan leadership for crimes committed during the civil war in 2011 will likely remain with the ICC. There have been some calls in Libya for domestic trials, yet it is unlikely that Libyan authorities will be able to challenge the ICC’s jurisdiction by demonstrating their ability and willingness to carry out trials according to international standards. Domestically, Libya will need to address the many lower level crimes committed during the war, which do not fall under ICC jurisdiction, as well as those that have been committed during Qaddafi’s rule. Ensuring a credible and fair domestic transitional justice process will seriously test the reformed Libyan judiciary in the years to come.

Analysis

During the coming post-conflict period, Libya and the international community will be confronted with a number of challenges related to the ICC’s investigations.

The first challenge is arresting war criminals. A number of former members of the Qaddafi regime have been arrested by the rebels, but they have not been indicted by the ICC. So far the ICC has issued three arrest warrants, but all three suspects remain at large:

- Muammar Qaddafi, the Commander of the Armed Forces of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and holding the title of Leader of the Revolution, and as such, acting as the Libyan Head of State;

- Saif Al-Islam Qaddafi, Honorary chairman of the Gaddafi International Charity and Development Foundation and acting as the Libyan de facto Prime Minister;

- Abdullah Al-Senussi, Colonel in the Libyan Armed Forces and current head of the Military Intelligence.

Soon they might be captured, killed, or they might flee to a third country – each scenario entailing its own set of difficulties. If they are arrested in Libya, pressures will quickly mount for Libyan authorities to extradite them to the ICC. If they die in combat, questions might linger whether they were executed and Libyan society would forego the benefits of a fair public trial, which outweigh possible risks. Lastly, if the three indicted leaders escape to a third country they might try to be granted exile there. ICC States Parties, however, are obliged to extradite individuals indicted by the ICC. Niger, an ICC State Party and neighboring country of Libya to where a number of Qaddafi loyalists have fled, has already pledged to cooperate with the ICC. Algeria, Libya’s neighbor to the West, on the other hand, has signed but not ratified the Rome Statute and thus has no such obligations.

The second challenge relates to the ICC investigations in Libya. So far only three members of the Qaddafi regime have been indicted. While more arrest warrants might be issued by the Court, Human Rights Watch has recently criticized the ICC for having bypassed major perpetrators and crimes in its previous investigations in Darfur and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Recent reports have indicated, however, that rebel forces may also be responsible for serious crimes. Amnesty International has reported indiscriminate attacks against black people suspected of having served as mercenaries for the Qaddafi regime as well as of reprisals against Qaddafi loyalists. ICC investigations would have to establish whether such acts were carried out in a systematic way, following an order by rebel leaders. The ICC only prosecutes those individuals that bear the greatest responsibility for the gravest crimes.

The third challenge concerns the location of trials in the context of the recent war in Libya. At this stage, the most likely option is a trial at the ICC in The Hague. If Qaddafi, his son, and Mr. al-Senussi are captured in Libya, the ICC will demand their extradition to The Hague where they would have to stand trial. Domestic trials are not likely for the time being. Challenging the Court’s jurisdiction would require Libyan authorities to formally lodge a challenge with the ICC and to demonstrate that they are willing and able to prosecute these cases domestically in fair proceedings. It is very doubtful that the Libyan justice sector would be capable to fulfill these criteria at the moment.

A possible compromise solution, paying tribute to the legitimate desires of the Libyan people to see their former leaders tried on their own soil, would be to hold ICC trials in situ, i.e. in Libya. Ambassador Wenaweser cautioned in this regard that “Such trials would likely be very expensive (for security and other reasons), and the cost implications would have to be studied carefully.”

Finally, even though a detailed discussion is premature and beyond the scope of this analysis, as Libya rebuilds, it will have to address the long and violent legacy of the Qaddafi regime. The ICC mandate does not cover crimes committed during more than 40 years of dictatorship. There are many precedents for how transitional justice can be handled – both from the African continent and beyond. Libyans themselves should determine which institutions/processes they deem appropriate in the coming months.

The Economist recently quoted rebel leaders committed to fair trials of members of the Qaddafi regime. However, the credibility of the new leadership will, to some extent, depend on its ability to deliver on this promise and on the extent to which it is willing to investigate and prosecute atrocities committed by some of its members during the war.