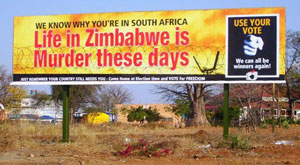

In the South African border town of Musina, a billboard encouraged Zimbabweans who left to go back and vote. (Sokwanele/Flickr)

“Do I believe rule of law will be restored? Absolutely, I do,” said Zimbabwean human rights lawyer Beatrice Mtetwa about her home country, which in March 2013 passed a referendum on a constitution that includes more human rights, though there is little political will to implement it.

She said, “if the people of Zimbabwe agitate for respect for that constitution”—94% of whom voted in favor of the referendum—“the rule of law ought to be restored in my lifetime.”

But she also spoke of another obstacle besides political will: money. The constitution, she said, “has all these grand rights where people are entitled to all kinds of economic and social rights, but these are rights that cost money.” And unless Zimbabwe is able to convince multilateral agencies to give them assistance, it would be impossible to give people those rights, “because the money simply isn’t there.”

Zimbabwe has long been one of the worst countries for human rights, and Ms. Mtetwa has long been an ardent defender of those rights, often at her own peril. She has been assaulted by police and arrested, which she said is what happens to human rights defenders in Zimbabawe. “Generally, there is harassment—we do get beaten up from time to time, we’ve faced arrests from time to time, and generally it has been made very, very difficult for us to do our work as freely as we ought to be able to.”

This year, she stood trial from June to September, before she was acquitted on charges of obstructing justice and being unruly to police officers. She has been locked up in a women’s prison, and described what happens when there is an appalling lack of toilets, clothes, and beds—people are dehumanized.

Ms. Mtetwa said human rights defenders are often lumped in with their client’s causes. “The fact that you may have your own opinions, but believe that the person is entitled to legal representation because what they are doing is allowed by the law, completely escapes those in power,” she said.

She said the judge who ordered for her to be released “was immediately attacked, he was harassed, he was threatened with an inquiry into his conduct.”

“So, what it means is that a judge who gets a case like mine will be afraid to do the right thing because they are scared of being attacked themselves. And for that reason, we really now require political will for the judges to be able to do their job the way they’re supposed to.”

“Probably like everywhere else in Africa, when you are a human rights defender, you’re generally perceived as an enemy of the state,” she said.

The interview was conducted by Priscilla Nzabanita, research assistant in the Africa program at the International Peace Institute.

Listen to interview (or download mp3):

Transcript

Priscilla Nzabanita: At the Global Observatory today we are pleased to have Zimbabwean human rights lawyer and activist Beatrice Mtetwa.

My first question for you is: you’ve dedicated your life to defending those who speak out against infringements of the rule of law and human rights by those in authority. Can you tell us what challenges you face as a human rights defender in Zimbabwe and in general?

Beatrice Mtetwa: Well, probably like everywhere else in Africa, when you are a human rights defender, you’re generally perceived as an enemy of the state. So, you do face those challenges of being seen to be fighting the state, when in fact all you’re doing is to try and ensure that people enjoy basic rights that are usually guaranteed even by the country’s own laws.

The problem that we face in Zimbabwe as human rights defenders is just the space—we do not have the freedom to do our work the way we’re supposed to. Generally, human rights defenders, who are lawyers, in particular get identified with the causes of their clients. If you represent certain persons, you’re perceived to be approving of whatever they are doing. The fact that you may have your own opinions, but believe that the person is entitled to legal representation because what they are doing is allowed by the law, completely escapes those in power.

Generally, there is harassment—we do get beaten up from time to time, we’ve faced arrests from time to time, and generally it has been made very, very difficult for us to do our work as freely as we ought to be able to.

PN: Picking up on the issue of arrest, you were recently acquitted of charges of obstructing the course of justice. Do you feel you were vindicated by the acquittal?

BM: I probably wouldn’t use the word “vindicated” because in my view I ought not to have been arrested in the first place. In fact, the arrest shows that doing the work can have those dangers. I was called out to a client’s premises who had police searching [them], and I got there and I asked for a search warrant. And that was my crime—I shouldn’t have asked for the search warrant. But, anybody who walks into someone’s home surely must produce a search warrant that shows what it is that they are investigating, and what it is they are entitled to look at—because a man’s home is his castle, you know.

If someone just walks into your home, they ought to feel free that they can call a lawyer to defend them and ensure that whatever search takes place is done legally.

So, I wouldn’t say I feel vindicated. I just feel that I had eight months of my working life wasted. Because during the eight months I was defending myself, I could’ve been defending somebody else who had a more substantive case than was alleged against me. So, I feel more annoyed by it, particularly because it has been shown to have been a put-up job.

PN: What are some of the challenges that women face in the prisons in Zimbabwe? What kind conditions are there? And what kind of support groups are there for women in prison and outside prison? What happens when you leave prison?

BM: Well, having been an inmate in March when I was arrested, I was quite horrified by some of the conditions in prison. I know prisons because every year, we have prison visits as lawyers for human rights—but visiting and actually being an inmate are two completely different things. I actually think that every human rights defender must go to jail, especially the lawyers, so that you know where your clients go when you fail them.

You get in there, and the amenities are just completely insufficient for the number of women that are in there. I was put in a cell with eighteen other women. It’s a very, very small cell. It clearly was never meant for that number of people. You get locked up at 3:00 in the afternoon—there is no toilet or any other pollution facilities in that cell—and they unlock the room in the morning at 6:30. So, from 3:30 in the afternoon to 6:30 the following morning, you are locked in this room where there is no toilet, there is nothing. And of course there are no beds.

So what the women do is fashion little containers where they do their business throughout the night. I was lucky when I went there because one of the new churches had just donated new blankets, so I was lucky that I got new blankets from that donation. There are no beds or mattresses or anything on the floor. And of course, the diet is absolutely awful. There aren’t enough uniforms. I had to organize to get a prison jersey made from outside prison and I had to buy it because the prison couldn’t issue me with one. And things like toilet paper, soap, etc., you can only just dream about that. So, women share whatever they get from home—sanitary wear is in short supply. And because of the congestion, obviously diseases are very easy to spread.

There’s virtually hardly any support system particularly made for women. There is ZACRO, which is an association that is supposed to look after former prisoners, but it’s not specific to women, and it does not have many funds and doesn’t have a lot of support, so really, there is absolutely no support whatsoever for women.

I was horrified that the women actually don’t even have educational facilities in prison. The men can study; they can further their education while they’re in prison but on the women’s side, what was supposed to be a library was full of all the junk. So, you can’t even further your education. There is no skill that you can learn now from prison. I know that in the ’80s you could learn how to type or sew, etc. All of that is gone. There is absolutely nothing. Other than going out to work in the fields, there is no other form of activity that women get engaged in.

PN: Thank you so much for that answer and now, just changing track, talking about the new constitution in Zimbabwe, which provides for a wide range of human rights under the declaration of rights—do you think there’ll be an impact in halting the human rights abuses now that they have enacted a new declaration of rights under the constitution?

BM: Well, I don’t really think so because the people who will interpret those rights remain the same. You can have a new constitution but if it’s going to be interpreted in a way that will deny people rights, it’s not going to have any impact.

The view I take is that really to have had a completely new dispensation required that we have a completely new Constitutional Court, which is manned separately from the Supreme Court, and definitely by different judges from the ones that have been there before. But what has happened is that before the constitution came into effect, there was a rush to appoint new judges, and those are the very same judges who denied people—even under the old constitutions—rights that they could have easily enjoyed. So I don’t necessarily believe that there will be any difference at all in the interpretation of the rights in the constitution.

But maybe it’s too early to say. Maybe—who knows?—somebody might wake up and think, “Ah, well, now we must give the people of Zimbabwe some basic rights.” We should know pretty soon how they will be interpreting the rights, because there are cases that we are bringing under the new constitution to see how these rights are going to be interpreted at a practical level. But sometimes we found that even if you win in court, if the powers that be do not like the particular decision, Parliament can change the constitutional provision and ensure that those rights are not actually enjoyed. And we know that currently ZANU-PF is in majority in Parliament, so it wouldn’t be that difficult for them to really ensure that they bring in changes to the constitution on anything that they don’t want to implement.

We also have the practical problem that we’ve got this new constitution, it has all these grand rights where people are entitled to all kinds of economic and social rights, but these are rights that cost money. And we know that the government is absolutely and totally broke. And it has all of these competing interests. So, even at a practical level, unless Zimbabwe is able to convince the multilateral agencies to give it money for certain of these basic rights, it would just be impossible for them to, in any event, give people in the short term those rights because the money simply isn’t there. So, there would be need for external assistance in that respect.

PN: So, my last question would be that you’ve said in the past the rule of law is the most important thing because virtually every aspect of a country is anchored on the existence of and respect for this principle. What do you think it will take to restore the rule of law in Zimbabwe, and do you think this will happen any time soon—in your lifetime?

BM: I believe that it will take the political will, because we’ve had contestations in Zimbabwe where you can see that it’s the power of the political antagonists. If we have political will, it won’t be difficult for judges to do the right thing because they’ll feel safe. You talk of human rights defenders as being under attack. Actually, it’s more than just human rights defenders because even people who don’t regard themselves as human rights defenders… if you get a judge, for instance, who wants to give rights, they can be antagonized for that reason. And they become a human rights defender by default, and therefore, because of that, they get targeted.

When I was arrested in March this year, the judge who gave an order for me to be released was immediately attacked, he was harassed, he was threatened with an inquiry into his conduct. Everything that you can think of was dredged so that he would already be seen as someone who ought not to have done what he did. And all he did was to hear a case and determine that there was no basis for actually locking me up. And the court vindicated him because a completely separate magistrate heard the case and dismissed it, even without me having to give evidence, because at the close of the state case, she said there was absolutely nothing showing that I had committed the crime.

So, what it means is that a judge who gets a case like mine will be afraid to do the right thing because they are scared of being attacked themselves. And for that reason, we really now require political will for the judges to be able to do their job the way they’re supposed to.

Do I believe rule of law will be restored? Absolutely, I do. I believe that the people of Zimbabwe are demanding it in the strongest possible terms and saying we have a constitution which we made with Zimbabweans as party to that constitution-making process. And they held a referendum on the 16th of March and said this is what we want to govern us going forward.

I believe that if the people of Zimbabwe agitate for respect for that constitution, the rule of law ought to be restored in my lifetime. I should enjoy that in my lifetime because it’s—as you correctly point out in your question—it is the anchor for everything else you do. You are not going to have economic development without the rule of law, because nobody will want to come in and invest in your country. People must have confidence in your justice delivery system if they are to come and invest in your country. You are not going to have business that works if people do not believe that, amongst themselves, there will be a fair process of determining disputes if business gets into disputes. And just generally, if you want a society that functions, you must have an independent judicial body that will be able to enjoy the confidence of the people.

PN: Again, thank you very much. It’s a pleasure and an honor to meet you, and we are very pleased that you are here with us.