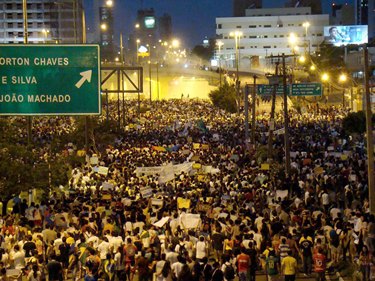

A public transportation fare increase in many Brazilian cities triggered mass protests against the government such as this one in Natal, Brazil, June 30, 2013. (Isaac Ribeiro/Flickr)

Around the world, governments are experiencing a “crisis of legitimacy.” The popular discontent found from Tahrir Square to Kiev’s Maidan, Bangkok to Brasilia, New York’s Wall Street to Hong Kong’s financial district all share a common ethos that leaders and governments aren’t listening to their people.

Whether the result of corrupt officials, weak institutions, or repressive regimes, widespread disillusionment comes with high risks for security, development, and democracy. In some places such as Iraq, it has helped foster extremism and violence. The question is: How to make governments and institutions more accountable, more inclusive, and more responsive to the needs of their citizenry?

In recent years, concerned development actors have responded to this disconnect with the “good governance” agenda of the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and other aid organizations. While important, these efforts are only a drop in the bucket in what has become a global challenge which, it is now clear, will require a commensurately global response and commitment.

At this pivotal moment, the post-2015 development agenda presents a potentially powerful tool that could catalyze positive change. With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set to expire in 2015, international negotiators are pushing for governance to be included within the post-2015 MDGs framework, also known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In July, in an important milestone, the Open Working Group for the Sustainable Development Goals submitted its proposal for a new set of 17 goals covering a variety of economic, social, and environmental issues. One of these goals is building “effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels” as well as ensuring “responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making.”

Although the SDGs will need to be approved by the General Assembly and may undergo further revisions, this proposal begs the question: What might the inclusion of a governance indicator in the SDGs mean for the development agenda, for governments around the world, and more broadly, for democracy?

What it Means for Development

The first round of MDGs, adopted in September 2000 by over 180 countries, enshrined eight different development goals focused on issues such as education, healthcare, poverty, and the environment, without any goal on governance. Soon after the MDGs were passed, however, development actors realized that their effective implementation required good governance in practice, if not in principle. For instance, disease cannot be eliminated without capable public institutions able to deliver lifesaving social services.

As early as 1997, the World Bank highlighted the link between governance and development in its World Development Report. UNDP took this a step further when it spoke of the need for not just good governance, but “democratic governance.” This underscored the belief that only participatory institutions and processes can truly understand—and be accountable to—the needs of the people.

To advance these piecemeal efforts, the SDGs would comprise a universal blueprint that states and development agencies everywhere would follow. This normative framework would come with concrete targets to which nations would pledge their commitment. As always, the devil is in the details, since agreement would have to be reached on what the appropriate targets and associated benchmarks would be. Fortunately, a variety of empirical metrics have been developed that allow for the possibility of measuring and monitoring governance, something that was not possible 15 years ago.

What it Means for Governments

An expanded SDG framework could mean a greater financial commitment toward projects designed to reduce corruption, improve delivery of goods and services, place checks on public officials, promote the rule of law, and expand the space for civil society and citizen participation. While some countries worry this will “crowd out” more conventional development goals, proponents argue it would have a multiplier effect across the development goals.

Unlike the first round of MDGs, in which the majority of the obligations were placed on developing countries, both developing and developed countries might be affected by the inclusion of a governance indicator. For instance, the advances made by the West in reducing child mortality and ameliorating poverty have not made them immune from declining rates of participation in electoral politics, low levels of trust in public figures, corruption scandals, and movements such as Occupy Wall Street or the Tea Party.

Meanwhile, the great strides made by rapidly developing BRICS countries in areas such as education and healthcare have often come at the expense of inclusive and transparent politics. Corruption, bribery, and opaque decision-making are endemic. A governance indicator would mean that all of the above countries would bear some responsibility. Implementation, of course, remains the key challenge: Are exclusionary governments truly willing to fund or pursue reforms that might check their own power?

What it Means for Democracy

This would also represent a striking shift from the first round of development goals, in which countries rejected language explicitly endorsing governance, let alone democracy. Wary of violations of national sovereignty, many countries felt that requiring states to adopt a specific type of governance structure was a bridge too far.

The current language used in the proposed SDGs may represent a kind of political compromise. Countries such as China are unlikely to accept explicit rhetoric on democracy given their historic resistance to the idea and the conflation of democracy with Western-style governments and US actions in the Middle East. Less politicized is the idea of effective, accountable, and participatory institutions, something few countries would object to.

If over 190 countries unanimously agree to work toward “participatory and representative decision-making,” this could signal a larger consensus on the importance of democratic governance, whatever label it is given. Along with bottom-up pressure from citizens, a more permissive normative climate for democracy at the multilateral level might help to explain why countries would rally behind a governance indicator this time around.

On balance, the inclusion of governance in the post-2015 development framework has the potential to be an important tool for bridging the credibility gap between citizens and their governments, at the very least galvanizing support for this cause. Of course, it is an entirely different question whether governments will strive in good faith to deliver on this pledge. No doubt citizens around the world will be paying close attention.

Michael R. Snyder is a Research Assistant with the Center for Peace Operations at the International Peace Institute.