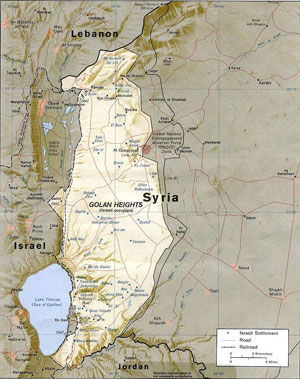

In June 2013, Syrian opposition forces attempted to take control of the Syrian side of the Syria-Lebanon-Israel border, and in particular, the Quneitra border crossing, recognizing its strategic and symbolic importance. More than a year later, they finally succeeded. On August 27, the al-Nusra Front, the al-Qaeda affiliate Syrian organization, took over the Syrian side of the border-crossing after fierce fighting with the regime’s army and abducted 45 Fijian United Nations peacekeepers, releasing them on September 11 only after Qatar paid a large ransom. The Irish and Filipino battalions of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) were spared a similar fate thanks to the direct involvement of the Israeli army which, by providing intelligence and guidance, helped them cross the border unharmed into Israeli-controlled Golan Heights. This week, more UN forces withdrew from the Syrian side as armed groups made further advances on peacekeepers’ positions.

Twenty miles north in Lebanon, there is increasing concern the activities of the al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State will surge in ‘Arqub, an area on the northern slopes of Mount Hermon, and in particular, the village of Shebaa, the largest in the region. The region has been hosting thousands of Syrian citizens who fled their country because of the civil war, and there are grave concerns in Lebanon that Shebaa might meet the same fate as Arsal, the predominantly Sunni village in northern Lebanon that, since early August, has been the site of a series of violent clashes between radical Islamists and the Lebanese Army, causing the killing of scores of soldiers, the abduction of nineteen others, and the public beheading of one them, dragging Lebanon deeper into the Syrian quagmire.

Historically, the border region where Lebanon, Syria, and Israel meet has been strategically important for the three states, and for non-state actors such as Palestinian guerillas (since the late 1960s until 1982) and Hizbullah. Since the 1920s, Mount Hermon has been a site of illicit cross-border activity between Lebanon, Syria, and Israel (and Palestine before 1948). The rugged terrain and its remoteness from the political centers in Lebanon and Syria have made it an attractive passage for border smugglers and guerilla fighters. Now, actors in Syria’s civil war are rediscovering its strategic importance.

Since the start of the civil war, the entire length of the Syrian-Lebanese border regions has been a site of cross-border warfare and refugee flight. Yet, the proximity to Israel at the tri-border region adds a level of complexity and volatility that is unique to this area. In addition, the presence of UN forces in the region (UNDOF has been in the Golan Heights since 1974, and UNIFIL in South Lebanon since 1978) has made it particularly sensitive for the international community and a coveted target for Islamist opposition organizations.

Israel is facing major challenges as a result of the al-Nusra Front’s takeover of almost the entire length of its border with Syria. The organization has not targeted Israel yet, but its ideological agenda undoubtedly makes this a possibility. Furthermore, the absence of a centralized state authority there makes the region particularly unstable. This border region was known for being mainly quiet since 1974 as a result of Syria’s strategic decision not to engage Israel there, but rather to use Lebanon as the prime arena of conflict with the Jewish state. This enabled Israel to deploy its army elsewhere and keep its military presence along the border with Syria at the Golan Heights to a minimum. This reality has clearly changed, requiring Israel to reconsider the deployment of its army and allocate more forces to the Golan Heights at an inconvenient time, given the security challenges in the Gaza Strip and the mounting Palestinian civil unrest in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Because the capture of the Quneitra border crossing is of great symbolic importance, there is no doubt that the Assad regime will go to some lengths to recapture it. Despite the disintegration of Syria, the regime has made efforts to demonstrate that it is still sovereign, and there is no better place to illustrate sovereignty and state control than at border crossings. If Hizbullah participates in the attempt to recapture the border crossing and the rest of the south of the country as part of its strategy to support the Assad regime, Israel, then, would face a new challenge where its nemesis could be deployed not only along its border with Lebanon, but also in the Golan Heights.

Paradoxically, perhaps, Hizbullah could become a stabilizing force along the border, at least for the short term. Whatever the case, the Assad regime, even as a backer of—or now more precisely, backed by—Hizbullah, is seen these days in Israel as a potential stabilizer along its border with Syria. This was patently evident when on August 27, Israel allowed a war plane of the regime to attack the al-Nusra Front’s positions in Quneitra. In any other context, it would have been gunned down or chased away for flying too close to Israel.

These recent events in the Golan Heights and the Mount Hermon region remind us that, despite the apparent military successes of the Assad regime (particularly in the north), there are no signs that the civil war is close to an end. Furthermore, while the international community has paid attention to the spillover of the Syrian civil war into Iraq, particularly through the territorial gains of the Islamic State, the events in the Golan Heights indicate that not only Israel could be drawn into the war, but also Jordan. The Hashemite Kingdom is already under extreme pressure because of the 600,000 Syrian refugees it is hosting in camps that are breeding and recruitment grounds for Islamist organizations, but it could be further threatened by the military presence of the al-Nusra Front along the Syrian-Jordanian border areas.

Lebanon, long entangled in the Syrian civil war, with over one million Syrian refugees hosted in the country, and with border areas that pit supporters and opponents of the Assad regime against each other, is now becoming the new site of Sunni Islamist extremists who see this small country as a new arena of their war against “infidels.” Reports abound about Christian Lebanese arming themselves in preparation for the worst to come. Not far away from the village of Shebaa are Christian and Druze villages that are obvious targets for Islamists. Should the ‘Arqoub become a new ground of Islamist militancy, as is feared in Lebanon, these villages might be targeted first, and the already fragile confessional balance in Lebanon would be further shaken.

It has been three and a half years since the start of the civil war in Syria, and the international community is paralyzed, unable to offer any constructive steps toward reduction of violence. There is no place for effective peacekeeping forces in Syria now, as the case of UNDOF demonstrates. If the civil war seeps into south Lebanon, UNIFIL might also lose its relevance. The establishment of the American-led coalition against the Islamic State reflects the unfortunate fact that the Middle East is moving from bad to worse. The tri-border region of Syria, Lebanon, and Israel is not lagging behind.

Asher Kaufman is Associate Professor at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.