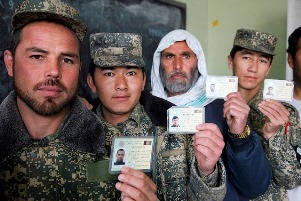

Voters hold up their identity cards, as they wait in line at a polling station in Kabul to cast their ballots on Apil 5, 2014. (UN/Fardin Waezi)

Afghanistan’s presidential election has reached its most decisive phase, with preliminary results of the June 14 runoff election between Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani expected July 2. Though this second round was held, according to initial observer reports, under generally similar conditions as the first round, the fact that there can now only be one winner has radically altered the political environment. There is a sense of crisis instead of euphoria, and dangerously deepening political divisions instead of the sense of national solidarity that followed the first round.

The first round on April 5 yielded one of the best good-news stories in the past decade. Turnout was high; Taliban violence was less than many feared; and the institutions worked. Afghans were able to feel proud of what they had accomplished. The final results of the election were in some ways ideal from a political perspective. They yielded two clear front-runners—Abdullah Abdullah with 45% of the vote, and Ashraf Ghani with 31.5%. While numerous complaints were filed, there was surprisingly little criticism of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) and the Independent Electoral Complaints Commission (IECC). This can be explained by the fact that the two front-runners did not want to undermine the legitimacy of results they were content with, and the other candidates in the field of eight were so far back that contesting the results was pointless. Because no candidate received 50%, there could be two winners in the first round, which significantly calmed the political environment.

What has happened? Almost immediately after the runoff election, Abdullah began a campaign to discredit the Independent Electoral Commission, alleging that massive fraud denied him votes, calling on his supporters to take to the streets and suspending his cooperation with the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC). This campaign was given credence when his campaign released tapes of phone calls in which the IEC’s Chief Electoral Officer, Zia Amerkhel, allegedly arranged to stuff ballot boxes. Abdullah called for Amerkhel’s resignation and for the election to be re-held in certain provinces. Amarkhel indeed resigned and Abdullah hinted that he would re-engage with the commission.

The IEC, in the meantime, decided not to release partial preliminary results, but is still expected to release full preliminary results on July 2. That is the day to watch. Unofficial reports—including a statement by Abdullah himself—indicate that Ghani has a significant lead in the second round. This unexpected reversal is the likely reason for Abdullah’s campaign against the electoral process.

As is often the case in Afghanistan, evidence can easily be found to sustain opposing interpretations of any given event. It is possible that fraud favoring Ghani was a major factor in his second round surge. But there are also more benign explanations, which include a Pashtun mobilization in favor of Ghani; a better organized campaign; as well as the possibility that the many endorsements Abdullah received from former civil war leaders reduced his popularity among a young and forward-looking electorate. One lesson from the first round seemed to be that elite power does not translate into voter influence as easily as it once did.

The only fact that matters is that a stand-off has been shaped. If the results released on July 2 show a significant Ghani lead, then Abdullah will face a series of unpalatable options. But there are really only two ways that this can end. Either the verdict proclaimed as a result of the decisions of the electoral institutions is respected by the loser, or the country will enter a period of prolonged political uncertainty, constitutional erosion, and possible conflict. The international community can and should provide technical assistance so those institutions act with a maximum of credibility and transparency, as it did in 2009. An electoral verdict can be correct without being perfect.

Diplomats in Kabul are understandably scrambling to find a solution that would accommodate both candidates. The usual template of a president-prime minister combine will surely be trotted out, with the prime ministry—a post that does not exist in the constitution—handed out as a consolation prize to the loser. Pseudo-Orientalist rhetoric about “face-saving” should be expected to justify this or other possible non-institutional arrangements.

If this moment is decisive, as I suggested, it is because it will determine whether or not Afghan leaders have truly adopted the logic of democracy—as Afghan voters seem to have done—or whether the source of power is ultimately non-institutional, negotiable, the result of behind-the-curtain deals, and permanently dependent on international arbitration.

Dankwart Rustow defined democracy as “that form of government that derives its just powers from the dissent of up to one half of the governed.” The true test of this final phase belongs to Afghanistan’s dissenters. If losers determined by the electoral process must also win, then the democratic process, however imperfect, has been a rather expensive waste of time.

Scott Smith is the director of the Afghanistan & Central Asia program at the United States Institute of Peace.